Former Riverside tandem chasing down their hoop dreams

Published 11:45 pm Friday, January 2, 2015

By ARI KRAMER

Special to L’Observateur

Most parents name their newborns. Harold and Karen Woods are not most parents — at least they weren’t in 1994.

Karen bore identical twin boys that December, and the family’s firstborn, Kayla, pinpointed a pair of names for her younger brothers.

“We were choosing between Trevor, Trevin, Trevon, Trevod,” Harold says, his Bahamian accent seeping through the phone. “She just said, ‘Why don’t you call them Trevin, Trevon?’”

“She came up with the name, and our parents were just like, ‘OK,’” Trevon (pronounced treh-VAHN) says, shrugging his shoulders.

“We don’t have any better names,” Trevin (pronounced treh-VIN) says with a chuckle.

Nearly 20 years later, Trevon and Trevin Woods share everything but the same first name — a dorm room, friends, gaming systems. They share the same basketball team, as they always have, now at LIU Brooklyn. The fifth letter is one of the few differences between them.

Trevin’s voice is slightly deeper, and he speaks faster. Trevon’s voice is slightly higher, with a mildly gravelly tone. He speaks slower. Trevin’s dark hair is clipped closely. Trevon’s rises about an inch off his scalp, and a sparse crop of dark hairs dangles from his chin. It’s a relatively new style for Trevon, who used to keep the same short hairdo as his brother. When they rock the same haircut, it’s nearly impossible to distinguish one from the other.

Says older brother Lavon: “It’s really just, like, when you pick up the phone and you hear your mom, you know it’s your mom, right? It’s this innate thing where if I hear his voice or I see his face, one has a rounder face and one is slimmer. One has a deeper voice. The other doesn’t have as much of a deep voice. You can tell them apart.”

Lavon is in the vast minority, joined by Kayla and the twins’ other older sister, Kayleesha. Not even Harold or Karen can consistently identify the twins correctly.

Harold, whose cataracts and several unsuccessful surgeries have rendered him legally blind, relies on his ears. That can prove fruitless, too, but even before he lost his vision, he had trouble distinguishing Trevon and Trevin by sight.

“When that system would break down,” Harold says, “what I would do is I would just say, ‘You.’ I’m talking to one of them. It had to be Trevon or Trevin. I would say, ‘Then go tell your brother.’ I would make sure if I was talking to Trevon, and I wanted to speak to Trevin, Trevin would get the message and vice versa.”

“They don’t try,” Trevon says of his parents. “They’ll be like, ‘One of you, come here.’”

“If we try to switch,” Trevon continues, “and I’ll be like, ‘Mom, I’m Trevin,’ she’ll be like, ‘Don’t play with me, boy.’”

“Or,” Trevin adds, “she’ll be like, ‘OK, if you’re Trevin, go do it. I need one of you.’”

“They try to play that trick,” Lavon says over the phone from his home in Los Angeles, “but they can’t trick me, in terms of which one is which.”

But they could delude most everybody else — from their parents to teachers to opponents on the court.

The Byrds

They also tricked Timmy Byrd into thinking they were good basketball players — according to their word.

Byrd, the head coach at powerhouse Riverside Academy, watched Trevon and Trevin play basketball when they were in eighth grade. The twins impressed him, and Byrd recruited them to his highly regarded program in 2010.

“He saw us at our middle school,” Trevon says, “and he was like, ‘I want those kids,’ and me and Trevin didn’t know why because we were terrible when we were young …”

“Just disgusting,” Trevin interrupts.

“Terrible,” Trevon emphasizes, elongating the first syllable. “He just really liked us. He said we had potential, and from there we didn’t ask any more questions.”

The twins were exceptionally tall as eighth graders — approximately 6-foot-3, according to Trevin. Though Harold doesn’t scrape six feet, the cousins and uncles on Karen’s side stand in the neighborhood of 6-foot-3 or 6-foot-4. Karen also starred for Florida International University’s women’s basketball team, and her pregnancy with Kayla curtailed her professional aspirations, according to the family.

Height and basketball coursed through the gene pool, and Trevon and Trevin have sprouted to 6-foot-6.

Harold ascribed the twins’ self-underestimation to a propensity that has clung to them since they were young.

“I don’t know why they would think — they’re so critical of themselves. I guess when you’re so critical of yourself, you can’t see the greatness in you,” Harold says. “Everyone else was telling us, ‘These boys can really play sports — baseball, football or basketball.’ People would say, ‘These boys have potential to make it.’ That’s what they would say.”

As residents of St. Charles Parish, the twins commuted nearly 30 miles to Riverside Academy’s campus in Reserve. They teamed up with Baylor’s Ricardo Gathers and Southern Mississippi’s Cedric Jenkins, among other future college ballplayers, in their one year under Byrd.

But it was another Byrd — Timmy’s father — that impacted their growth as basketball players the most. His name was Daddy Byrd. The twins can’t recall it, but others knew him as Ronnie.

“[Daddy’s] what stuck with us,” Trevin says of the man who passed away shortly after the Woods family moved to Texas in 2011. “I know I’ve heard his first name before. Not that I don’t care, but I think it wouldn’t fit.”

“He’s a dad,” Trevon says before Trevin joins him in unison, as only identical twins can do. “He’s like our second dad.”

Daddy Byrd’s age was as much of a mystery to the twins. They remember him as an older man whose age was belied by a feverish ardor for basketball and educating the game’s youth. He also saw potential in Trevon and Trevin and prescribed a daily regimen of 100 pushups and 100 situps, encouraging muscular generation without lifting weights.

“He would always check us every month,” Trevin says as he pats his brother’s chest, “and be like,” Trevon, smiling and nodding, joins in unison, “‘Yeah, you’re getting bigger.”

Daddy Byrd fostered an insatiable work ethic in the twins, who live by his modus operandi, “Excuses are for losers.”

Says Trevon: “We would be like, ‘But coach, Ricardo Gathers is 250 pounds of pure muscle —”

“Pure man,” Trevin interrupts.

“‘And we’re just 150 over here, just skin and bones, coach.’ He would be like, ‘I don’t care!’”

“Excuses are for losers,’” Trevin interjects, again.

“You can block that! Don’t let him dunk on you! Box him out!’”

If Daddy Byrd’s coaching techniques seemed harsh initially, Trevin says he and his brother understood the intent in time.

“It wasn’t that he was yelling at you, but he was encouraging you,” Trevin says. “You got the message instead of getting the criticism.

“That guy was the most influential guy in our entire lives.”

The twins have a tendency to speak in superlatives. Daddy Byrd certainly had a profound impact on their growth as basketball players, but they would be remiss to divert credit from their parents and older brother.

“They tagteamed to get us to shoot well,” Trevin says.

Trevon elaborates: “They used to kick us out of the house at 8 or 9 in the morning and we couldn’t come back until about 10 at night — just to shoot outside. You couldn’t leave the yard. Friends couldn’t come over. It was just you and the rim —”

“Just you and the rim,” Trevin emphasizes. “It’s a good thing we were twins because that,“ Trevon joins in unison, “would have been torture by myself.”

If Daddy Byrd was a tough critic, Harold was impossible to please.

“I would always try to be the devil’s advocate and keep them grounded,” he says.

“Our dad doesn’t say anything good,” Trevon says. “If we won a championship then he’ll say something good. He’d say, ‘Good job.’ If we scored 20, it’s, ‘Why didn’t you score 25? Why didn’t you score 30?’ He believes in the black and white.

Tough Times

Trevon, Trevin and the Woods family faced a stiffer challenge in the two years preceding the twins’ enrollment at Riverside Academy. In January 2008, Harold underwent surgery in Louisiana to repair a detached retina, one that had been detached and reattached time and time again.

“The doctor botched my eyes up,” Harold says of the January procedure.

Eight months later, Harold underwent the same surgery at NewYork-Presbyterian Hospital in New York City’s Washington Heights. His retina was successfully reattached. His vision, however, failed to return.

Not only would he never see his twin boys play for Timmy Byrd — or any coach thereafter — but he would also have no choice but to close the mortgage business he and Karen had opened in 2006.

“After my surgery, I lost my bond because I could not keep up with all my bills and stuff,” Harold says. “My credit started to go south. In order to keep a bond you need a credit score above a certain level, so I had to close the door.”

The family had endured hardship in 2005, when Hurricane Katrina chased them northwest to Lafayette for a few months. But Harold does not view that time with contempt.

“We were all together,” Harold says. “Everybody was together as a family, so there wasn’t really any hazardous effect.”

And their home, which sat perched on a hilltop in St. Charles Parish, sustained minimal damage during the storm.

“It was a blessing that we could come back and recoup, unlike some of the people in New Orleans, with the levees breaking and all that water,” Harold says. “It was never like the people in New Orleans.”

In the year-plus after Harold closed the mortgage business in 2009, family eased the pain again. The older siblings supplemented their parents’ financial needs as they could.

“I think it just put a strain on everything,” Lavon, a software engineer, says of the impact on his brothers’ lives. “At that stage … you want certain things and you’ve had a certain lifestyle and you’ve had certain things and you want those things that a lot of other kids have, whether it’s a cell phone, clothes, whatever. You have to make certain sacrifices.”

Said Trevon: “It was just a realization because you’re used to a certain way of living and then it gets taken away from you. It’s just, you have to adapt to it.”

Their basketball lives did not change, though.

Even though he couldn’t see, Harold would still train his sons, in quasi-Samurai fashion.

“If he couldn’t hear the net whip,” Trevin says…

“Then you weren’t making it,” Trevon finishes.

“He would be like start over,” Trevin adds. “We’d have to make 10 in a row or 20 in a row. He would train us like that. Now that I say that out loud it seems pretty crazy. He used to literally pull up a chair, sit outside, not underneath the rim but near it.”

A moral foundation established by Harold and Karen guided the twins during that time. The twins still hark back to their parents’ teaching to “never quit.”

“Just keep moving forward because winners are not quitters,” Harold explains. “If you expect to be a winner you can’t quit, number one. You have to stay in the fight.”

The entire Woods family did just that — the twins with basketball, the parents with an uprooting.

In 2011, Harold and Karen moved the family to Sugar Land, Texas, a suburb of Houston. Trevon and Trevin enrolled as sophomores at Austin High School. Their parents purchased a food trailer and sold Bahamian cuisine, as they pondered how to resurrect their livelihood.

“That’s what we did to demonstrate to our kids again that you don’t quit,” Harold says.

The twins did not embrace the move, initially. Their friends were in Louisiana, in what Trevin calls “a movie-type cul-de-sac.” They would hang out in each other’s houses, go skateboarding or do the things that young boys do, like getting into trouble. Trevin remembers playing one-on-one against Trevon with a bouncy ball in Wal-Mart, using the fragile ball cage as the hoop.

“Trevon once dunked and he broke the fence and all the balls came flooding out,” Trevin says. “They were like,” Trevon joins in unison, “‘Okay, you guys got to get out.”

The Lone Star State

Moving to Texas introduced the twins to a different basketball culture, a grittier one. They worked out with several high school basketball players at a camp held by former NBA player John Lucas their first week in the Lone Star State.

“We came in and people were just, like, growling at us,” Trevon says. “We were like, ‘What? What are y’all doing?’”

The twins recall Lucas running a one-on-one drill. Trevon and Trevin would switch off trying to dribble by a scrawny but feisty kid named Isaiah Taylor, now a sophomore point guard for Rick Barnes’ Texas Longhorns.

“[Lucas] told him, ‘Don’t let them move,’” Trevon recalls.

“We had the ball,” Trevin says, “and our job was to just get past the guy—“

“Just an inch,” Trevon interrupts.

“For like 30 minutes we kept rotating and the guy would not let us go anywhere,” Trevin says.

“That was our first real taste of Texas basketball,” Trevon adds.

It wouldn’t be their last.

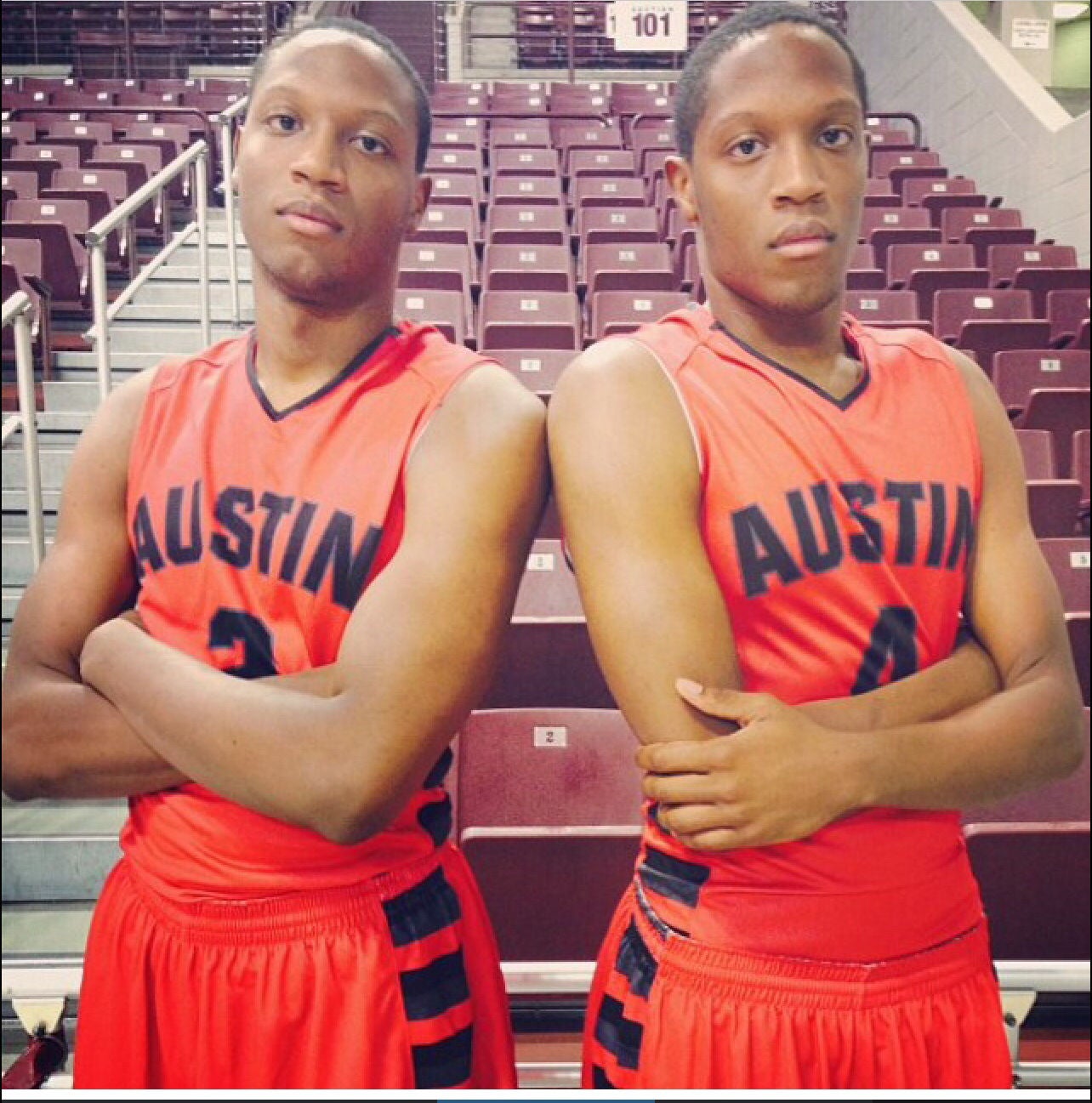

Trevon and Trevin starred for Austin High. In three years they never made the state playoffs, but they helped resurrect a program that had not even competed for a postseason spot since the mid-1990s.

Playing in Texas, they said, they learned to never discount an opponent because of his physical appearance.

“In Louisiana, you saw a guy and you saw what he looked like and that’s pretty much who he was,” Trevon says. “In Texas you never could sleep. You were getting surprised everywhere you looked.”

In a late-season game with playoff implications their junior year, an opponent’s unlikely hero nailed a game-winning three-pointer.

“The guy nobody scouted, he won it,” Trevon says, shaking his head.

“It was with like three or four hands in his face,” Trevin says. “All of us jumped at him. We even fouled him, and he still made the shot.”

The Rise

While the twins learned to never overlook their foes, they also flew under the recruiting radar.

Their performance on the 2013 AAU summer circuit changed that.

That’s when Jack Perri first saw them play, and he walked away with the opposite impression the twins thought they left on Timmy Byrd.

“Oh, they weren’t terrible,” LIU Brooklyn’s coach says, laughing at the thought that anyone could have ever reached that conclusion.

Perri took his seat in Duncanville High School’s Sandra Meadows Memorial Arena one day that July, and watched the Woods twins go blow for blow with Emmanuel Mudiay and Malik Newman, top recruits in the classes of 2014 and 2015, respectively.

“[Trevon and Trevin] were shooting threes all over the place, off the bounce, dunks,” Perri says.

“They just went off,” Lavon says, laughing as if he’s still in awe. “Trevon I think had, like, 30-something points and Trevin had 30-something points. They were just shooting the lights out from everywhere on the court, defending [Mudiay]. They had no respect for him in terms of his persona or whatever his ranking is and just went and competed and that was special to see that they just rose to the challenge and competed on that level with that team.”

Says Perri: “It was like, oh my God. This is an easy one. They’re 6-foot-6. Can they play a frontcourt spot at our level? Will they play guard? They were versatile, which is what we recruit. They could pass dribble and shoot, so I was excited about them right off the bat and I just followed them around the rest of that tournament.”

Other coaches shared Perri’s sentiments after that game. The Woods twins each received offers from Texas Tech. Arkansas and Alabama expressed serious interest, and Kentucky, Missouri, Kansas, Southern Methodist and Penn State were among several other programs that at least reached out.

But they all viewed Trevon and Trevin as the same player. They weren’t exactly wrong. Trevon and Trevin are identical twins, after all.

“They all wanted us separately,” Trevin says.

Not Perri.

The twins, who complained about the inconvenience of living in different rooms in the same suite while taking classes this summer, barely considered shipping off to different schools. They had to be together.

And together they are, sharing a dorm room on LIU Brooklyn’s campus this semester.

“It’s better this way because we can actually talk to each other, especially if he annoys me or something,” Trevin says. “I don’t have to knock on the wall. I can just go over there and punch him in the face.”

Don’t worry. He’s kidding. Maybe.

Either way, it definitely wasn’t a brotherly brawl that sidelined Trevon for several practices leading up to the season and the opener at St. John’s. He played nine total minutes in the Blackbirds’ losses to Saint Joseph’s, Stony Brook and Temple.

Trevin had seven points on 3-of-5 shooting in the overtime loss to Saint Joseph’s. He added eight rebounds and two blocks in 22 minutes. In LIU Brooklyn’s other three games, he totaled six points, six rebounds, two assists and a block in 41 minutes.

The Woods twins haven’t exactly burst onto the scene like they did on the 2013 AAU circuit. But they have embraced the challenges the college game presents to freshmen — the size and athleticism of opponents, the speed of the game, the level of preparation for each contest.

They have frames that could develop into exceptional college bodies, especially in the NEC. They’re athletic, and, like Perri noticed immediately, they can shoot, dribble and pass.

Attitude problems have curtailed the careers of many promising prospects with similar attributes, but that shouldn’t be the case for Trevon and Trevin.

“They’re superstar kids,” Perri says.

They’re humble — respectful of players of any size, thanks to their experience in Texas — but confident.

Daddy Byrd taught them that only losers spew excuses. Harold and Karen showed them that winners don’t quit.

And they won’t quit. They have a plan.

At the very least, basketball will help them earn a college degree — Trevin in computer science; Trevon in media arts. It could also be a source of income, as their goal is to play professionally after college. Their first paycheck — or at least a significant portion of it — will be addressed to Harold and Karen Woods.

“They give us everything,” Trevon says.

Everything except names.

“We,” Trevin adds, “are going to make sure we repay them.”

Ari Kramer is a New York-based writer who covers the MAAC, Ivy League and NEC for One-Bid Wonders. Follow him on Twitter @Ari_Kramer.