Walter Hernandez remembered as one of the brightest minds to come out of St. John Parish

Published 12:10 am Wednesday, September 21, 2022

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

LAPLACE — Walter C. Hernandez was in the first grade when he felt a light bulb go off in his head, and from that point on, there was nothing presented to him in math and science that he wouldn’t understand. With an unbelievable appetite for knowledge, he was perhaps one of the greatest minds to ever emerge from St. John the Baptist Parish.

Hernandez recently passed away, leaving behind much more than a prolific career in relativity and hydrodynamics. Those closest to him remember not only his patents and inventions, but also how he was a man of integrity who valued family above all.

His younger sister, Suzanne Mastainich, recalls that Hernandez had a way of making everyone feel comfortable.

“My brother’s word and a handshake was, to him, as good as a written contract. He was honest and very trustworthy, and he probably paid for it in the long run,” Mastainich said. “He never made the fortune he could have made because others took advantage of him, but he was always very down to earth. He never bragged or put anyone down if they were not as smart. He wanted to be one of the regular guys.”

Hernandez obtained his PhD and worked with several different companies, and there are many products he invented that aren’t in his name. However, a quick Google search of his name reveals several patents.

His nephew, Aaron Hernandez, remembers him demonstrating an early invention that measured heart rate around the wrist long before FitBits or Apple Watches were on store shelves.

His youngest brother, Tommy Holmes, recalls that Hernandez had a nearly photographic memory that served him well.

According to Holmes, one of his inventions made strides in signal processing technology. A box set on a vehicle could accurately detect the presence of an animate being inside an inanimate structure.

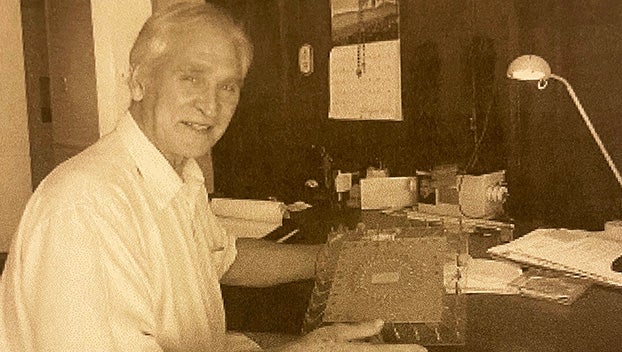

Aside from items like coolant pumps and electrical generators, Hernandez also invented a pen-sized object that used signals from gear boxes to detect defective equipment and predict what was going to break next in a factory setting.

The last invention he worked on through the 2000s and 2010s, called “The Dew,” showed promise as an alternative to traditional windshield wipers. Without utilizing any moving parts, Hernandez tested a prototype that used electrical fields to prevent water from obstructing glass.

“The Navy, Air Force, government are all interested in this technology,” Holmes said. “I think it all started with the Navy having the periscopes on the submarines, and they would get a film of water on them.”

Few would guess that Hernandez rose from very humble beginnings, having spent his childhood working in the fields and picking crops such as okra to make money. His family moved to LaPlace while he was in elementary school. He quickly became known for his brains and his brawn when he attended Leon Godchaux High School in the 1950s.

Hernandez loved listening to music, so much so that he taught himself how to build and repair radios. His high school physics teacher, Mr. Frazee, thought the world of him and would often hand Fernandez the textbook and ask him to explain concepts to the class.

Sometimes he ended up teaching the teacher. Mastainich recalls Mr. Frazee knocking on the door to their family home with the textbook in hand, walking to the back room and saying, “Walter, show me how to do this.”

When Hernandez graduated as valedictorian from Leon Godchaux High School, his name was called for almost every award until another student finally claimed the English category.

After high school, Hernandez took the entrance exam at LSU and scored so high that he was suspected of cheating. Local legend says the staff asked him to take a second test, and he scored even higher. Mastainich said it wasn’t true that he was forced to take a second test, but the instructors did speak to him about his unusually high score. That year, he went on to win the freshman physics award at LSU.

While attending undergrad, Hernandez inadvertently scored a track and field scholarship while training his younger brother Ronald to throw the shot put. Hernandez could never outperform his younger brother in track, but his throw was impressive enough for a coach to offer him a spot on the team.

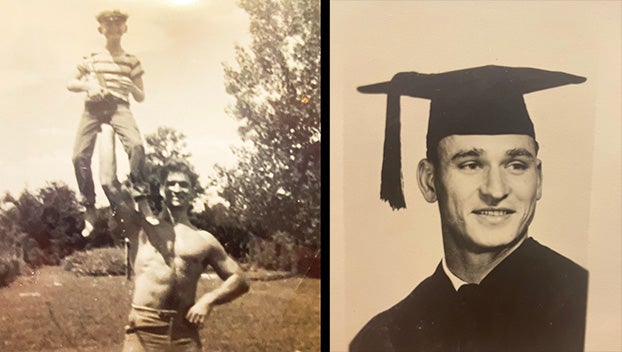

Hernandez was also a body builder who earned first runner up in a contest in Washington DC, and his strength matched his physicality. One treasured family photo shows Hernandez easily hoisting his youngest brother, Tommy, up into the air with just one hand.

While Hernandez wasn’t a fighter by nature, longtime St. John residents still remember a legendary brawl he got into at the Fourth of July Fair in Reserve during his high school days. A boxer from up the river who went by the name “Eagle Beak” punched Hernandez in the mouth. He responded by picking Eagle Beak up off the ground and throwing him across the hood of a car. It’s been said that when the police arrived, they shook Hernandez’s hand and said, “that kid has been needing that for a long time.” Eagle Beak and Hernandez later made amends, and their families grew close decades later.

While Hernandez said his heart always remained in South Louisiana, he was drawn out-of-state to pursue graduate schooling in physics and astronomy at the University of Maryland. There, he was selected as the first-year graduate student who demonstrated the greatest promise for a career for fundamental research in physics. In 1966, he received a personal postcard from the Freie Universitate Institut Fur Theor. Physik in Berlin, Germany, along with a request to forward his research.

Hernandez settled in Maryland and started a family. His son, Adam, said it was apparent his father was a hero to his hometown. He kept family first and talked openly about his faults, but admitting to his imperfections only made him seem more heroic in his children’s eyes.

His sister-in-law Cathy Homes remembers Hernandez as a gentle-hearted man. Soft like a lamb, he could be brought to tears by both happy and sad occasions.

He was also rational, and he was known for sharing two pieces of wisdom gained from his own mother: “Believe none of what you hear and half of what you see” and “Don’t make decisions when emotional.”

Even though he was only in town once a year, often for the Ory family’s grand New Year’s party, Hernandez never let go of his roots. He told his sister that his biggest regret in life was leaving South Louisiana. If he could do it over again, he would have stayed close to home and taught at LSU.

Friends and family are invited to a memorial service being held at Petra Restaurant from 2 to 5 p.m. on Sunday, October 23.