Survival in words: Eunice Gauthier’s letter

Published 6:00 pm Sunday, June 26, 2022

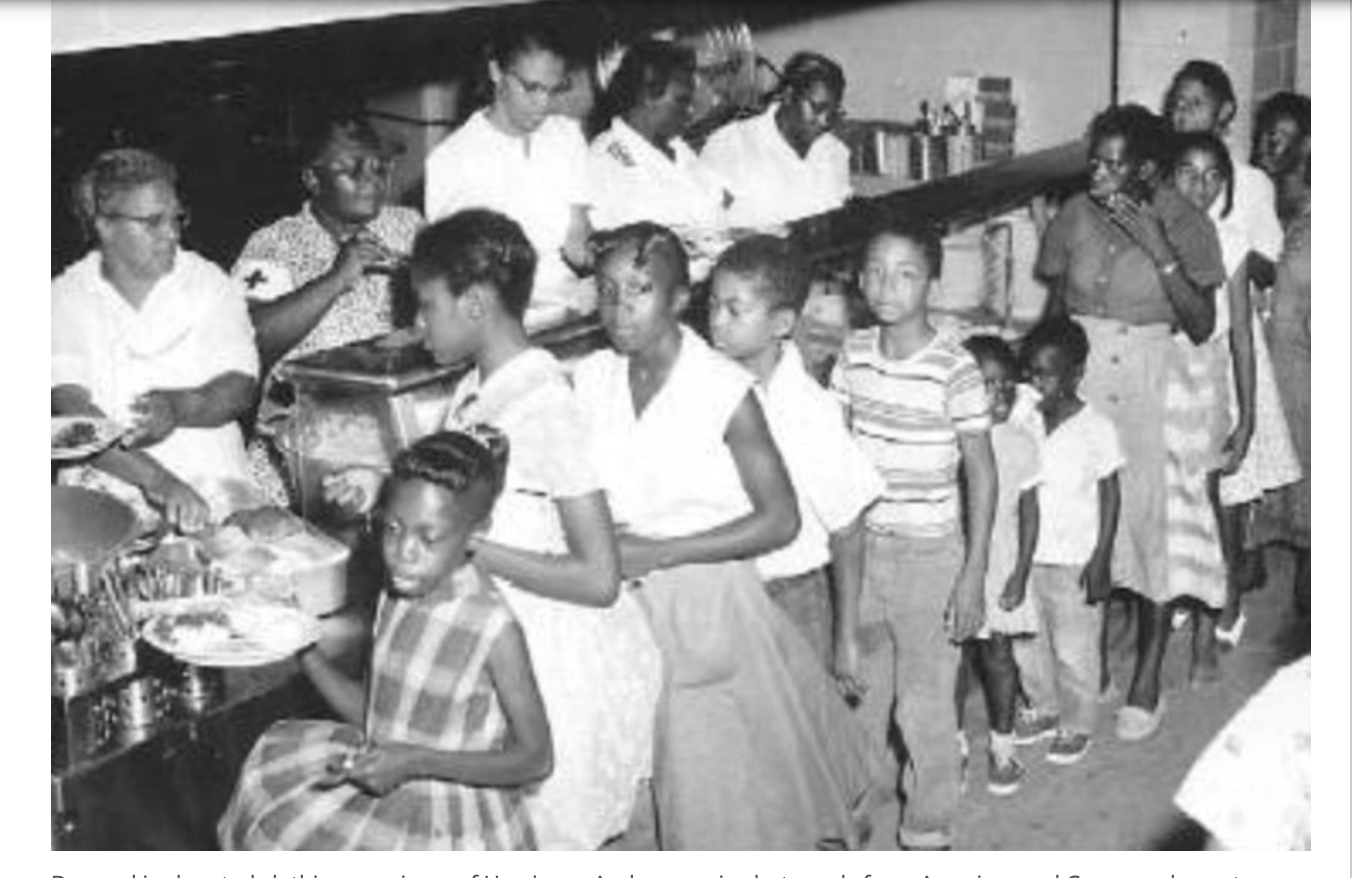

- Dressed in donated clothing, survivors of Hurricane Audrey receive hot meals from American red Cross workers at a shelter set up in Lake Charles after the hurricane. (Special to the American Press)

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

Today is the 65th anniversary of the monstrous Hurricane Audrey making landfall in Southwest Louisiana. The coastal hurricane would claim some 390 lives — the exact number has never been determined — and leave $150 million in damage on its path of destruction.

Recorded as the most powerful June storm in the Gulf of Mexico at the time, Audrey formed in the Bay of Campeche as a tropical storm on June 24, 1957, and two days later intensified into a hurricane in the southern Gulf of Mexico.

Many lives were changed by the fierce storm, which left many people homeless — and desperate. One woman, Eunice Gauthier, lost her home and belongings to Hurricane Audrey’s fury. She and her daughter lived through the hurricane and later sent a descriptive letter to C.R. Faith in Shreveport describing their horrific encounter. The following is an excerpt from that letter, which vividly describes her experience.

Eunice Gauthier’s letter

“Wednesday we got warnings that the hurricane was 350 miles south of Cameron and heading toward Cameron at seven miles per hour and would probably reach Cameron about 6 Thursday evening at winds around 100 miles an hour. By the time they (Mr. Gauthier and a daughter, Imogene Park) got home the warnings were a little oftener and she decided she’d go into Beaumont with the baby. So after consulting we all decided that we’d all get up early and Gus would drive Imogene in her car and stay with the boat in Lake Charles, Mrs. Park would come over and get Imogene and the baby, store Imo’s car and we’d go to Jimmie’s.

After they hung up, Imogene says, ‘Daddy, 1 know you and Mrs. Park mean well, but I’d have a hunch that we’d better get out tonight. If it were only me I’d ride it through with Mama and Julia Anne but I have him to think about.’ So Gus says, ‘Well, you can’t go alone. I’ll take you to Beaumont and bring your car back, come back, see about my boat, then come on and get your mama and Julia Anne and go to Jimmie’s. So they left.

“Julia Anne and I listened, but the warnings were about the same, they never urged all the people to get out, they only urged the people in the low areas. Finally, we went to bed and at 2:30. I woke up and turned the radio on. It said it was getting closer and would probably hit Orange about 10 the next morning (Thursday). Gus hadn’t gotten back, so I thought then about going to Jimmie’s, but thought Gus would soon be in and went to reading. Soon the lights went off and I dozed off to sleep.”

“l awoke and saw that Gus wasn’t in and I worried about a wreck. Then as I was thirsty I put my foot down — in water — and it was knee deep all over the house. Our beds were floating as they were Hollywood beds in that room and very low.

“I awoke Julia Anne and told her that it had happened before to me and that it would soon go down, etc., so she didn’t get excited. I explained to her that we might have to get on the roof, and we went about putting things up higher. We couldn’t budge her $700 piano, but put her horn up high, also her new Singer sewing machine, her luggage, record player, TV and Imogene’s cedar desk.

“By then, the water was almost to my hips so we decided to get dressed. All our clothes were wet at the bottom so we then decided to put on our bathing suits. I ate half a sandwich but couldn’t persuade her to eat. I did make her take two big drinks and took several myself because I told her we might be on the roof several hours. By then the furniture was bouncing and I was afraid we’d get hit — so I suggested that we go on the back porch, where there was no wind. We almost didn’t get the door open.

“It was after 8 when we got on the porch. As the water was getting too deep for her, I cut the screen out with a broken piece of furniture that floated up and got her ready. I told her what to do and to not lose her head but to lie flat when she got up there. Just then, a big gust of wind came and blew the framework in for the screen.

“I told her it was time to grab the TV aerial, which she did, but couldn’t climb for her foot would slip. I calmly held it and told her to step on my hand and boost herself up, which she did, but when I tried I slipped back down. When she didn’t see me, she started hollering — and I scrambled up enough so that she could see my head and told her I’d have to wait down until the water got deep enough for me to get on the roof and lie flat.

“Well, about that time the wind began blowing things against me. I saw that I couldn’t wait. I tried to step on a ladder that blew near, but it wouldn’t give enough boost before it would go back under, then be blown back against me. About that time, my big refrigerator — porcelain enameled inside and out, a 13-footer — was swimming around in the kitchen. It bumped against the wall and pushed the wall out. At that instant I saw it and booted myself up on the roof by stepping on it and holding to the TV aerial.

“I lay flat on my stomach beside Julia Anne. Just then a gust of wind took the opposite roof and deposited it upside down within 2 feet of us. Then the roof over Imogene’s room flipped around and disappeared altogether, leaving the attic. When this took place, the roof we were on (the kitchen) separated from the living room roof and left a six-foot gap of attic open and collapsed onto the attic floor.

“The TV aerial then decided to leave us. It whirled around as if it would fall on us and then fell opposite. We then came to the network of cables that went to the micro-wave station in back of our house — and had about a foot clearance which I knew wouldn’t allow our bodies to go under … the corner of our house hit the pole, pushed it and the wires down just low enough for us to go over the cables.

“Then we were pushed along for five miles over that marsh for a ride. We couldn’t enjoy the scenery, because we had to put shingles over our heads to protect our eyes from the rain and flying particles, and lie on our stomachs flat with nothing to hold on to or another.

“The rain was beating our backs like pieces of glass and all the skin was rubbed off our legs, elbows and chests, but we lay in that position until there was a little let-up (around 4). We looked up a little and found we were wedged in between two banks of a bayou with bulrushes and a cow on each side, with the lake about 10 feet away on the side and the marsh covered with water on the other side.

“A little later we saw a plane go over. (I) figured that the worst was over, though we still had plenty of wind and still couldn’t get up to see. Finally, at dark, we got on a door and spent the night in the open.

“The next morning when the sun came up I knew where we were… we had been up there trout fishing… (but) unless someone who knew the lake came, they’d never get to us. Also, I knew that most of Cameron was gone and that helicopters were our best bet — but they couldn’t land unless the wind subsided! Oh, I lived a thousand years while that sun was beaming down on me and on my child. I prayed that if anything happened to either of us that it would be to me and not to her. She never looked so pretty or so precious.

“All the boats were about two miles away and didn’t slow up enough to see our flag. The planes patrolled between us and Cameron — only one came near us, and that was to take pictures. Finally about 1:30 we saw one coming from Cameron and I told Julia Anne that it was moving slowly as if they were looking for someone. We stood up and waved our flag, which they saw and came to us.

“Someone said, ‘Well, if it isn’t Mrs. Gus Gauthier and her daughter.’ So you know how we felt! He was Mr. Veasey, a boy who piloted one of our boats for three years. He was now working on an oil field rig in Hackberry and had told his boss that morning that he bet many people were out at that particular part of the lake and that no one could get in unless they knew the part — so his boss said, ‘I’ll get the company boat and we’ll go.’ They came to the courthouse and we saw Pewee (Gus’ brother) and started out looking for us, saw our flag and rescued us.

“When we got to the courthouse, everyone brightened up — because they felt that if we had survived, others might have. They rushed us to St. Patrick’s where there were no rooms, but they had improvised a school room — and I want to tell you that the Civilian Defense and Red Cross really did a wonderful job, along with the hospitals, doctors and volunteers.

“Julia Anne was in shock and of course I was worried. They doctored and watched over her, then that night two of the best nurse volunteers in Lake Charles, along with two sides, took care of our ward. And who should be ministering to me but Miss Edna Kaow — the nurse who saved my life before! Well, when she saw me, no one else could do a thing for Julia Anne and me. All night we were her special patients and when I told her how worried I was about Julia Anne and that our doctor was out of town, she had Dr. Emmitt come and give her another check and a shot for asthma, and had him check me again, though we both had been checked once.

“About midnight she told me that Julia Anne had passed the danger point and would not go into pneumonia or asthma, and by 6 a.m. she had located us a private room in the maternity department and had us moved from the ward.

“We stayed there until my own doctor came and checked us and told Gus it would be better for us to leave the hospitals, as my blood pressure needed to come down.”

Hope amid tragedy

Despite the horror of the hurricane, Gauthier found hope. She concluded her letter this way: “We’ve lost everything we had, but we feel like millionaires! The Lord was certainly with us every minute of the time and Julia Anne and-I felt that he was! We are not feeling sorry for ourselves, though things look low, but when I think of the people who are attending funerals this morning and of the mass funeral of unidentified that are being buried, I feel like getting on my knees and staying there forever.”